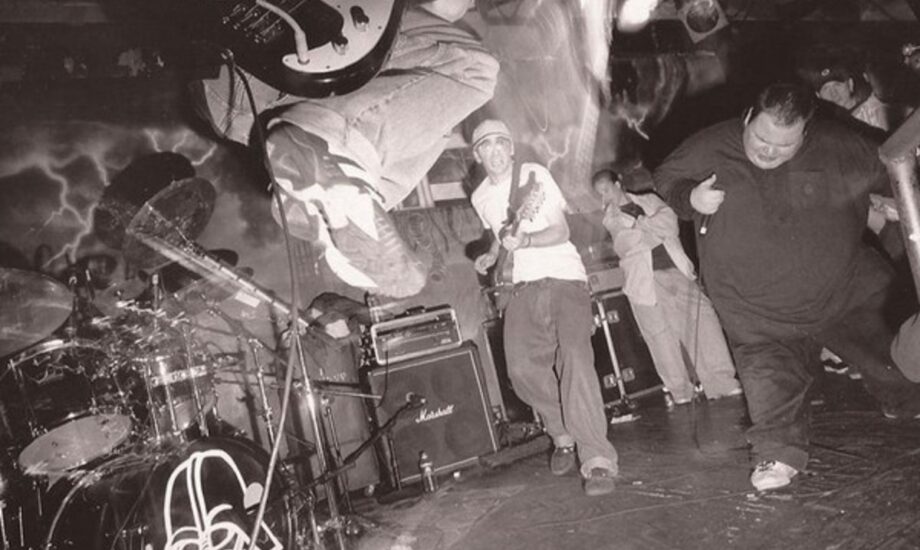

ALBANY—It’s impossible to talk about the Albany hardcore scene of the 1990s without mentioning Straight Jacket. Driven by dark, introspective lyrics, the band’s unique take on metal and hardcore was a staple of the region alongside such behemoths as Stigmata, One King Down and Section 8. With a handful of releases—including appearances on pivotal compilations like Common Ground and United We Stand—Straight Jacket became one of the more celebrated local bands, playing regularly at venues like the QE2 and Saratoga Winners.

On March 9, the core lineup of the band—Greg “Tiny” Kennedy (vocals), Thom Lytle (guitar), Sean Green (bass) and Joe Clark (drums)—will be reuniting for a one-off show at Empire Live in Albany, with guitarist Mike Comtois of Dissent notoriety joining on rhythm guitar (now with Anacortez). With the reunion coming up quick, Lytle, Green and Comtois took some time to talk about all things Straight Jacket.

COLIN ROBERTS: What sparked this Straight Jacket reunion show to happen?

THOM LYTLE: The reality is that everyone wanted to do one over the last handful of years; maybe the last 10 years. I don’t think any of us were totally aligned in our headspaces at any given moment, but this past year I started really getting the itch. I was one of the ones dragging my feet probably the most in the last five years or so; I’d be the first one to start the fire. I sent Green a text, upon which he had no idea who it was, which made it more entertaining.

SEAN GREEN: I hadn’t heard from the dude in 16 years and the last number I had for him was a New York number, so it just came up some number that I didn’t know with a random text. I was like, “Who the hell is this?”

TL: Yeah, but the sentiment of the message itself was, “Are we gonna run this back?” And after we identified who each other was, we basically started talking about who we could convince, who would need a little more convincing, and would we even have the physical ability to do what we did when we were teenagers at our young age of whatever we are at this point? We decided to give it a go; everyone was into the idea. We talked about how to pull it off remotely because we’re all living in different places, and the rest will be history. We’re excited for it.

CR: How has it been dealing with the logistics of preparing for this, being spread out?

SG: [laughs] Well, first off, I had to buy all new equipment because I stopped playing when I moved to Virginia. I stopped totally playing; I was in Brick By Brick for 14 years with [Mike] Valente and after that I was just done, and I was like, “I don’t even want to play,” and I sold everything. I didn’t have the itch anymore and I said in the back of my brain, “The only way I’m going to play again is with these guys; with Straight Jacket,” and thinking it would never happen again and then here we are. So I had to buy all new equipment and even just start playing again. I haven’t played in years; I haven’t even touched a bass in years. Lytle’s been good sending little tutorial videos to me and Mike and we’ve pretty much been on the honor system and just watching those and learning.

TL: I feel like I’m on Onlyfans, the amount of videos I’ve had to take of my midriff.

SG: I like how you change up the shirts, though.

TL: I had to have a wardrobe change just so you guys don’t think I’m recording them all in one day. But Mike [Comtois] here has the biggest task: We at least have a lot of this stuff rattling around in the backs of our brains and the backs of our fingers. Mike had to sign up. I don’t know if he knew what he was signing up for. We’re thrilled to bring him in on it, but he was signing up to basically pick up everything that Jim Brassard had done on rhythm guitar and it’s not an easy task, because these are songs that he wasn’t around writing and playing twice a weekend like we were. He’s done an awesome job.

CR: Mike, how did you get involved and how has it been for you to approach these songs?

MIKE COMTOIS: Sean just reached out, presumably after he touched base with Lytle about running it back and asked me if I’d be interested in playing. I just immediately said yes. I’ve been a fan and friend to the guys since forever. Sean and I went to high school together and I remember him handing out demos way back in the day. I have a lot of these songs built into my brain quite a bit. So it actually came a little easier than I thought it would. It’s a tall task, but it’s a fun one. It’s a challenge but I’m excited to do it and thankful to be on board, and I get to play with Sean again, which is really cool. I’ve looked up to the guys since I was a little guy, so it’s been really cool; I’m really excited.

CR: Is there a certain mindset you guys have to tap into to get into the mode of these songs?

TL: I’d say my musical experience of recent was more like playing “Jake and the Neverland Pirates” and all the kids tunes on my acoustic guitar in the house. They’re like, “Wait, you play guitar, dad?” about every three months when I would play something. I mean, it’s all there. That’s the thing; none of us here stopped loving the music that we played, but we certainly probably listen to some slightly different stuff at this point in our lives. But it’s all there, and as much as we joke that it’s a tough task or whatever, it’s like riding a bike. Once you figure it out it really comes back quickly.

We got together—Mike, myself and Joe [Clark], our drummer—in beautiful, snowy Vermont like a month or two ago just to start getting a feel for it live and it came back really quickly. I will say we’re thankful to have a drummer as ridiculously professional as Joe, because the dude is like his own metronome. He does not miss a beat that he had played in his original tracks back when he was 16-17 years old. It sounds exactly the same. As a lost guitar player, it’s easy if you had any other drummer to be thinking, “I have no idea what part’s coming up next; I have no idea where I am in the song,” but Joe just hitting every mark really makes you feel comfortable. And I bet, Mike, with you it also makes it… real with the absence of Tiny being there. Joe makes all those songs real.

MC: It’s kind of like, people know songs from vocal cues and where choruses are going to be. Joe’s drums are so specific to the songs, and they’re so catchy that it’s almost like having that as another mechanism for being dialed in. You just know where something is going to change.

TL: And he’s probably played more than three of us—Tiny, myself and Sean. Mike, I know you’ve been playing, but Joe has been playing all through this also. His chops are there; he’s ready. I tell you, anyone can probably replace any of us bums. Joe would be tricky. In fact, we almost did it once when we were playing a gig way back in the day with Section 8 or something. I think we had Tim Parent lined up to do it and then it fell through anyway. I think it would have sounded very different even with a good drummer like Tim, but we never had to entertain that idea.

CR: That’s interesting you say that about Joe, because looking back, it seems like all of the Albany bands back in that time had both unique vocalists and unique drummers as well. You listen to a Section 8 record or One King Down or Withstand, and the drums are something that really stuck out and helped make all of the bands sound different and unique.

TL: There’s only so many different ways you can play three chords, right? All joking aside, although I think we really avoided that quite a bit in our later stuff, but I will say with Joe, I love talking about the dude when he’s not here, but it’s all compliments. I think what set Joe apart from a lot of the hardcore drummers back then was he was raised like a rock and metal drummer. He and I were playing in rock and metal bands when we had long hair down to our back in pictures that we won’t show our wives nowadays. It’s just how he was raised, so he brought that into a lot of hardcore riffs and structures, and I think it gave it a lot more depth than maybe—not that there’s anything wrong with a hardcore band having all hardcore styles, but it sounded different, and I think that’s what stood apart from a typical hardcore approach back then.

CR: Do you remember the last Straight Jacket show?

SG: To take the high road on this, bands are like brothers, and sometimes you don’t get along too well, and sometimes things happen.

TL: 15 years is a long time that we get to figure out our perspectives on stuff.

SG: I’ll say this: our last show was doomed from the start, even before: We did a reunion show in the summer of ’07. We were like, “Ok, that was cool,” and we got asked to do a weird, private kind of show in Saratoga and Backstreet Billiards in December; it was around Christmastime. I actually had a show earlier in the day with Brick By Brick, so I had to go play that one and we had to play early on the other side of Troy, and then I had to get to Saratoga. So I think part of it was my fault in the fact that I wasn’t on time and the person that had a PA left or something. There was a PA thing; the guy left and they got this makeshift PA, but there was an electrical problem.

TL: Backstreet was in the process of being shut down. I believe they were off the power grid at that moment. They had stopped paying power.

SG: It was a generator situation, I think.

TL: I do remember Murph showed up with his PA equipment and was like, “I’m not plugging into that equipment.” About 15 feet that way, on the other side of my basement is the JCM 800 that I used that night that fried in the last song. Everything got blown out in the last song we played and that was the last time that I touched that amp. It completely fucked up my stuff and Murph was 100 percent right to not plug in.

SG: So anyway, we’re trying to be positive and move forward past that because it was so long ago, but it was doomed from the start; we wound up only playing to a handful of people by the time all was said and done. I don’t even know how many people were there, but it was nothing we planned on, and then things went from bad to worse all night and just got really bad. We fought and then that was it. I think we just kind of all left it at that. There was a little bickering and then it was just left for years; I think we all just walked away from it wiping our hands of it being like, “Well, that was that.”

TL: I would say this is not a do-over. This show really comes from a genuine place of us being essentially, “Whatever, let’s get back to basics.” We’ve seen now how complicated life can be, and what matters and what doesn’t. Plus we’re giving ourselves a better chance here. I think everyone was lazy approaching that show. We were lucky enough that, aside from Sean handing the Mikes of the world demo tapes in high school, we didn’t have to do promotion for ourselves. We took it for granted for a while.

SG: Very spoiled.

TL: Everyone was going to shows and it got tougher when people weren’t. So we’re taking care of this one to make sure people know about the gig and why were doing it, and even what you’re doing here is helpful just getting the message out on what it’s going to be and why we’re doing it.

CR: I want to get into the history and the development of the Straight Jacket sound, but I wanted to first ask Mike about what drew you to the band as a fan back then?

MC: Well, what’s cool is that Straight Jacket sort of took Dissent under their wing for a couple years there in like ’97/’98. So we got to see the full dynamic of the band. Besides Tiny’s uniqueness as a frontman, as a guitar player I was always into the guitar parts. I was always watching what Lytle was doing, what guitars he was using, stuff like that. So I found doing this kind of easy because that little bit of the Straight Jacket DNA was sort of in my playing just from absorbing all of that and being more of a guitar nerd back then than I am now probably. So I would definitely say the guitar stuff was a big draw for me, and the competition was pretty heavy. As a guitar player in a local band you had the Scoville brothers and Matt Wood from One King Down, you had Lytle, you had RJ [Pipino, Cutthroat], Mike Maney [Stigmata]…just ridiculous guitar players.

SG: Don’t forget Ian Zumback [End of Line].

MC: Oh my god, Ian Zumback, the king himself.

SG: I grew up with that kid from the get-go and that dude was playing Guns N’ Roses songs in ’87 note-for-note. We were kids looking at him in awe.

MC: He’s an animal.

SG: Still is.

CR: When did Straight Jacket begin, and how old were you guys?

SG: We started in early ’95, I believe.

TL: That would have put me at 17.

SG: I think we were actually 16, because I don’t think we turned 17 until later that year. I wasn’t even driving; I know I had to get rides to Saratoga.

TL: We went through this recently and I think learned from our mistakes—it’s a weird, convoluted background story that could be summarized as there just happened to be a show thrown where a bunch of us came together in separate bands and ostensibly realized we should be playing this kind of music with those dudes. There was a couple iterations of it, but once the tree shook out, what was left was myself, Sean, Joe and Tiny and we wasted no time. It moved quickly. I think we had four or five songs probably within the first week that all formed most of the original demo tape.

SG: Not to mention we had a previous singer to Tiny and we had six or seven songs then for a set that we might have kept maybe one, and then turned around and put another six-song demo out with Tiny in less than a year.

TL: Little known fact, I think, is “I Can’t Go On” is the oldest Straight Jacket song there is musically. Our previous singer singing on that song, we had a tape of it. That was the tape that, let’s just say politically, we all decided that was not the direction we wanted to go in after hearing that tape, and let’s just say Mr. Gregory Kennedy agreed and was happy to take the baton.

SG: I woke Tiny out of a sound sleep to ask him if he wanted to sing. I barged right into his apartment. I was like, “Hey, you want to do this?” He was like, “Uh, sure.” It just rolled that way.

TL: I couldn’t believe Tiny wasn’t snagged up for a band. Joe and I were coming from poorly informed metal roots up in Saratoga; Sean and Tiny knew the scene better, knew what worked and what didn’t. With Sean coming in with his Sick of it All, Cohoes-style, it all started to fit together really easy up front. Had it not, I’m not sure we would have really survived as a band, but it just fit together like puzzle pieces really early on. Just a reference for Jimmy Fresh—I think when we wanted our music to be a bit more dynamic, loud and big and could compete with the One King Downs—there was a lot of one guitar bands but we just wanted to sound bigger and more complex—we’re like, “How about that kid that just records everyone on video?”

SG: I had no idea he played guitar and I grew up with the kid.

TL: He was good, too. That was the crazy thing. He played quietly to himself because he was a pretty modest guy, and I think he would just probably crank out One King Down songs on his own and just jam, and he was very willing to do it. I remember the practice we brought him in. Just like Comtois—just knew all the songs. I didn’t have to say a damn thing. I thought it was going to be harder. Then we started writing a bit differently from that point on. With respect to the reunion, Jim is in full support of Mike. Mike doesn’t have to look behind his back.

SG: There’s no bad blood or anything like that.

TL: No, I think for a myriad of reasons he just didn’t know if he could pull himself up to do it, either through his guitar playing, or he didn’t want to go half-assed on it and pull us down. And I get that.

SG: Don’t worry, I got that covered.

CR: What were you guys into and what were you trying to sound like in the early days?

SG: I think we were listening to a lot of Integrity, a lot of Sheer Terror. At that time I was trying to show Lytle everything I could. Me and Tiny were just overloading him and Joe.

TL: Yeah, and I would say I liked a lot of it, but I remember thinking sometimes, “This fucking sucks. Everyone loves this, the technique of this sucks.” I had to get over myself and just understand more beyond the guitar riff for music when I started listening to hardcore. I was a latecomer to it. I’m from the Midwest; I grew up an ’80s hair metal kid.

SG: In all fairness I did too.

TL: I was into Pantera and Sepultura and Obituary and all those bands, and then learned I don’t have to have super long hair to play heavy music. I obviously knew about Helmet, but that was the extent of the you-don’t-have-to-be-a-stoner-long-haired-dude-to-play-metal experience. I was listening to a lot of Biohazard.

SG: Yeah, and Life of Agony, too.

TL: Correct. A lot of the Roadrunner bands. I liked the production of Roadrunner stuff. And I liked the production of EVR stuff. But with Life of Agony and Type O Negative, all that stuff that just had that weird, solid, crisp metal sound. That was the bridge into us. Our early stuff sounds like shit. I like the songs, but it’s like we’re playing a Lars Ulrich St. Anger. Love Joe, but we pulled a little bit of a St. Anger in our demo.

SG: That was my first time in a studio. We had a four-song demo that we did before that. We rented a four-track from a music store and recorded it in Joe’s garage in Saratoga.

TL: It’s the first time we recorded “Final Cry.” The first version was a bit more death metal-y, with blast beats. [Grade] has an album, I think it’s called The Embarrassing Beginning. I always loved the name of that, because over the years I’ve felt like every band has the embarrassing beginning and you can’t get away from it. It just is what it is. Sean gently reminds me often of what I think musically about some of the original songs should have less relevance than I think. Sometimes the simplicity and being in the spirit of those initial songs is what people care about. Like reminiscing about them.

SG: It’s the lyrics. Credit to Tiny. The lyrics on the demo are…pretty much it’s a suicide demo. But a lot of kids at that time, and even to this day I have people come up to me and say, “Those songs meant so much to me.” And it’s not like you’re listening to what the guitars doing, what the drums are doing; it’s the lyrics. Them being able to yell the lyrics. Tiny’s lyrics were very easy to remember. They weren’t complex; they were earworms. They got into these kids’ heads. His lyrics almost make them anthems in a way.

TL: That’s something we noticed very early on. Joe and I, it was just a guitar player and a drummer playing for years and we’d never had a frontman, and once we got Tiny it was like, “Oh, this dude knows phrasings, he knows choruses, he knows sing-alongs, he knows how to build the dynamics of a song.” Extremely talented, extremely professional. I agree with you, Sean, even in those old videos I’m singing my head off, not really paying attention to anything I’m doing. Those songs were like radio songs for hardcore kids.

SG: It was the words and kids couldn’t wait to sing along with them.

TL: The Straight Jacket first album was the Michael Jackson’s Thriller of hardcore albums.

SG: Kids just got it. I think they could identify with feeling out of place, feeling a certain way about certain things, you know?

TL: Who better to scream their story than Tiny, right?

CR: Sure, it’s introspective and identifiable. And you guys are labeled “Emotional Hardcore” on all these old flyers you’re sharing on Instagram. Did that emotional aspect inform the music you guys made too?

SG: Those tags were mostly [promoter] Ted Etoll. He had a lot of free reign on how he titled people. I think we were Paul Bearer’s offspring on one.

TL: I think people had a hard time describing what it sounded like and all they could really discern was this dude Tiny absolutely murdering his vocal cords singing the craziest, passionate stuff that is just awful, and all they could walk away with was, “This stuff is emotional.”

SG: He wasn’t just singing the words to sing the words; you could see in his face, he felt it.

TL: I remember thinking that emotional hardcore was viewed as a pejorative, and I remember thinking I love that word getting lumped into this, because we are completely opposite from most any notion of emo. I found it entertaining. To show up to a show, us four or five dudes looking the way we did, and everyone thinking, “Wait a second, is this supposed to be some soft Victory Records band from Upstate New York?”

SG: Like Shift.

TL: Yeah. But it was a bit of a Troy angle into Western New York hardcore mixed with Northern New York, Plattsburgh metal just all coming together into a big sloppy non-mess.

SG: We were four opposites that somehow clicked on all cylinders—four or five. You got a band like Neglect from Long Island that’s singing about suicide, but they’re nuts and they’re heavy. They talk about it in a harsh way, but Tiny crafted it in a way where he just felt it. I always hated the emo thing because like Lytle said, I always hated that people thought we’d come out looking like Weezer and playing some rock music. Here I am in JNCOs and an Integrity shirt down to my knees with a hundred chains on, and a chain wallet I could knock somebody out with and a padlock in my back pocket. Now, looking back it makes sense, but at the time I kind of didn’t like the whole emotional tag. I get it, but I didn’t want to be in an emo band.

TL: The funny thing is, unless you’re screaming about punching somebody else’s face in, you’re labeled as emo. Human beings are simple and that’s the way they tagged it, but it always entertained me. I figured, we’ll play and if you like it you like it and if you don’t, you’ll probably still stay around because we’re entertaining.

MC: Tiny is very poetic. His lyrics had that “guy really scraping into a notebook and singing that stuff.” That was always pretty cool from a fan perspective. Definitely emotional, but passionate. You could feel it.

SG: The funny part is we’d get put on a lot of shows with emo bands, too. Some of them were all right and some of them really just didn’t care for us. I remember playing with Shift; I remember playing with Autumn.

TL: Yeah, and they did not like us. They did not like when we would open those shows and I understand it.

SG: Yeah, now.

TL: I think they were turned off by it. They were supposed to be very introspective, spacey, shoegazey, thoughtful music.

SG: Yeah…Stillsuit; Mind Over Matter.

TL: Yeah, Tiny would come in and just go up to the crowd and not even need a PA at these shows, it was so loud.

SG: Yeah, we definitely clashed with a few bands. Not because we wanted to, just because I think it goes back to how we were labeled and the shows we were put on. They put Straight Jacket “emotional,” and we’d come on and we’d have all of Cohoes finest piling the stage, telling you to go fuck yourself.

CR: You guys were featured on two monster compilations for this region in Common Ground and United We Stand—and Mike, Dissent was on United We Stand, also—what did being part of those mean for you guys?

TL: I felt like we were like the person that was late to the movie. Everyone else settled in, they got their spots. Straight Jacket started later than all these bands for the most part, like the Section 8s, the Cutthroats, the One King Downs, so for me, anytime that we got lumped in with these bands, either on a show or in an album or compilation, I was flattered. I was proud. I was thankful. I just liked being affiliated because I was such a fan of the scene and I was proud of us in doing it in short time. We worked really hard up front to get that footprint and then I was super happy that everyone embraced it and liked what we were doing.

SG: Yeah, it was always an honor. I mean, Stigmata was always a staple, even when I was a kid. I always looked up to them; I went to high school with the One King Down dudes when they were Drown; Withstand was always a big thing for me. So to get a band—like Lytle said, we flashed forward quick. Straight Jacket hit the ground running. That demo came out and then it was, boom, Common Ground. Then it was, boom, the demo ’98, and then the self-titled after that. It just went up and we have Ted to thank a lot for that too. Ted took us under his wing, too—him and Section 8. Pretty much we could ask for any show and we got it.

TL: I don’t think there were many that we would be turned down from around that time.

MC: United We Stand was surreal for me. I felt like our band snuck into a club we weren’t supposed to be in and ended up on the list somehow. It felt really cool. I must’ve been maybe 16 when that came out and it was pretty wild. So to look back and see all the bands and listen to how terrible all the recordings are, it just didn’t matter; it was so awesome. It was a good cementing of local hardcore royalty at the time.

TL: United We Can’t Stand The Mix.

SG: I’ll one up you on that. It’s way better than the Capital Punishment mix.

TL: We even recorded some of these comps and it was never released. There was at least one or two of those things where we went into the studio and spent a Friday and a Saturday night and just never got anything out of it.

[At this point Thom has to leave to attend to parental duties]

CR: Continuing with the idea of those comps and the scene at the time, did you guys feel like you were a part of a special moment?

SG: Once Straight Jacket started getting its legs in like ’95/’96, and before us was the Cutthroats, the Withstands, the Stigmatas, the Dying Breeds, the War-Time Manners, the Politics of Contrabands, all that stuff. We came in a little later and then all of the sudden it was this influx of bands, and they were all doing something different, and it was all good. It’s hard to explain; all the cylinders just hit. You had a million bands and it was great, and the scene was thriving. Every outside band wanted to come in and play.

I remember opening a few shows for big bands and the crowd clearing out after we played. We opened up for Kreator at Winners and we brought the crowd, and after we played everybody left. We did it multiple times. I remember going to see Brutal Truth and Only Living Witness and Cutthroat at Winners. After Cutthroat 90 percent of the crowd left. That’s how it was; it wasn’t just with Straight Jacket, it was every band. Section 8 would open up for somebody and everybody goes to see Section 8 and stands out front or just hangs out and doesn’t pay attention to the national. It happened a lot back then and it was crazy.

MC: I would say that’s exactly why Dissent even started. I’m from Cohoes; Sean’s from Cohoes. You got Straight Jacket that’s half Cohoes; you got One King Down; you got End of Line coming from there. So everybody wanted to start a band. Everybody was always going to the shows, or one of these guys was playing at the high school for a battle of the bands or music night thing.

SG: Straight Jacket playing the Cohoes High gymnasium. I’ll never forget that.

MC: Lansing Park. I lived right across the street from the park, so I waddled over as a 14 year old and watched that go down. It was a way of life back then.

SG: I lived and died by that long handbill Ted would hand out every week. And Tiny was like our go-to with Ted, and we’d say, “Ask Ted to get on this show.” If it wasn’t full, we’d get on it. We played every other weekend. And if we weren’t playing we were there hanging out. It was a magical time. We didn’t make any money—nobody made any money—we just had fun.

MC: No one cared. It was just too much fun.

SG: I always look back and am glad my teen years were spent doing that. Do I wish the band got a little bigger? Absolutely, but I’ll be a local legend; that’s fine [laughs].

CR: Circling back around to the reunion show, you guys have got a stacked lineup playing with you.

SG: I worked with [Mike] Valente—we were bandmates for over a decade and we’re still on good terms—and I hit him up like, “I don’t know if this is going to happen but I just heard from Lytle after 16 years.” Him and I went through lists of bands. It’s not as easy as it was in ’96 to find a good crop of bands you want to do it [and] you call them up and they’re like, “Yeah, we’re in.” That’s not how it works these days. People are older; people got other responsibilities; people want money. It’s just what it is.

I have to give props to Valente for it. He and I would just sit there and brainstorm. He pulled Underdog out of nowhere and I was like, “You think they would do it?” We had another band lined up and they dropped. I’ve been friends with Sworn Enemy—those are my dudes, being in Brick By Brick—and I still talk to those guys. We went on tours with them and they were just my dudes, and they said yes and I was stoked. I wanted bands that had a connection to the past but are still relevant. Or like, Grand Street, they’re my friends. They’ve got Cohoes kids in them. Spiritkiller has Byron [Wheeler] who replaced me in Straight Jacket for a few years when I left, so that’s the connection there. Underdog is just a classic hardcore band. And Assault on the Living; Tiny and Dustin [Clapham] are like best friends.

CR: Mike, what are you looking forward to most?

MC: Playing with Sean again is going to be cool. The Dissent reunion was like 12 years ago now at this point. So, to romp around with Sean is going to be fun. To play upstairs at Empire [Live] is going to be cool. I’ve seen enough shows there now; it’ll be cool to check that off a list. I’m looking forward to seeing a lot of Cohoes kids I haven’t seen in a long time, but I’ve been bumping into people left and right who are like, “I’ll see you at the show.” So I’m looking forward to that spirit of reunion.

###

Straight Jacket will reunite for one epic night at Empire Live in Albany on March 9, with special guests Underdog, Sworn Enemy, Spiritkiller, Grand Street and Assault On The Living. Tickets can be purchased online here.